- +92 51 8990 873

- info@ngimpact.com

- DHA-II, Islamabad

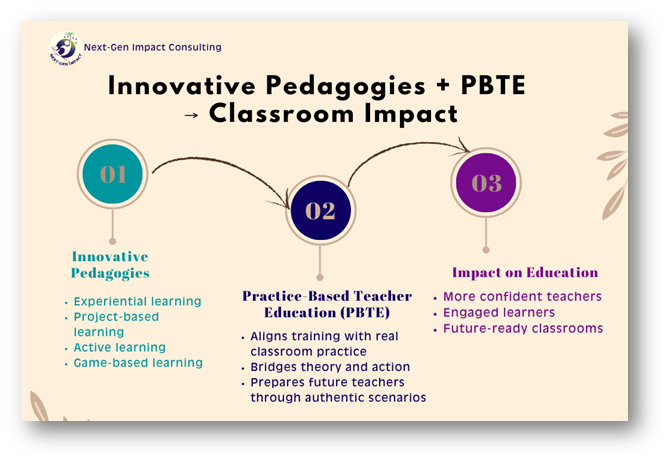

Innovative Pedagogies and Practice-Based Learning that Work in Real Classrooms

Education is catching up with what high-quality workplaces have known for decades: people learn best by doing. As classrooms evolve from passive lecture halls to active labs of thinking and making, four pedagogies stand out: experiential learning, project-based learning (PBL), active learning, and game-based learning (GBL). When these are coupled with practice-based teacher education (PBTE) , training that centers what teachers actually do in real classrooms, the result is not only stronger student engagement but measurable improvements in teacher skill and learning outcomes.

Traditional teacher education often emphasizes theory and content knowledge. While valuable, this is not enough. Programs that foreground enacting teaching practices, micro-teaching, rehearsals, and coached practice, show larger gains in teachers’ ability to elicit and respond to student thinking (Grossman et al., 2018; Ball & Forzani, 2021). In short: when teachers practice high-leverage moves in realistic contexts, they improve faster.

If future teachers experience the same inquiry-rich classrooms they are expected to create, and do so under the guidance of experienced mentors, the cycle of improvement accelerates.

Experiential learning: reflection plus action

Experiential learning involves structured experience and reflection, not simply “hands-on” activity. Learners move through cycles of action, observation, and reflection to transform experience into understanding (Kolb, 2015). Examples include service learning, community investigations, and simulations. Students gain practical skills and reflective habits, while teachers learn to design activities that connect doing with sense-making.

Project-Based Learning (PBL): inquiry with purpose

PBL organizes learning around authentic projects that solve real problems or answer significant questions. Systematic reviews confirm that, when scaffolded well, PBL fosters higher-order thinking, collaboration, and transferable skills (Kokotsaki, Menzies, & Wiggins, 2016; Hmelo-Silver et al., 2021). Projects also provide a natural platform for formative assessment and community partnership.

Active learning: small moves, big gains

Active learning covers strategies such as think-pair-share, retrieval practice, and peer instruction. Even small active-learning moves significantly improve attention, memory, and conceptual understanding compared with lectures alone (Freeman et al., 2014). For teachers, these strategies are low-barrier yet high-impact.

Game-Based Learning (GBL): motivation and iteration

Games structure focused practice, immediate feedback, and adaptive challenges, all central to effective learning. Evidence shows GBL enhances cognition, motivation, and social, emotional skills. The aim is not superficial gamification but meaningful, feedback-rich practice that transfers to real tasks.

The most resilient classroom designs integrate multiple approaches. For example:

Hybrid designs allow teachers to balance motivation, scaffolded practice, and authentic application, with multiple points for assessment.

Innovative pedagogies only work if teachers are prepared to enact them. PBTE shifts the model from abstract theory to deliberate practice. Instead of only reading about methods, teacher candidates rehearse them, teach in real classrooms, analyze video of their own work, and refine skills with feedback (McDonald, Kazemi, & Kavanagh, 2013; Zeichner, 2012).

For in-service teachers

For teacher education programs

Innovative pedagogies can widen gaps if not carefully designed. To ensure equity:

Scaling PBTE requires investment in mentor preparation, coaching infrastructure, and time for iterative practice. The payoff: better-prepared teachers and more equitable classrooms.

International forums such as IATED proceedings and MDPI’s Education Sciences special issues are amplifying evidence on PBL, PBTE, and technology-enhanced learning. These open-access platforms help educators access syntheses and design models applicable across contexts (IATED, 2022; MDPI, 2023).

The convergence of evidence for PBTE, accessible coaching technologies, and renewed focus on authentic learning creates a rare opportunity. When both teachers and students learn by doing, classrooms become spaces of curiosity, agency, and capability. Leaders must resist chasing fads and instead double down on evidence-backed practices, coaching systems, and cycles of enactment. The future of teaching is not about the next new method, but about turning powerful pedagogies into lived classroom realities.

At Next-Gen Impact Consulting, we believe the future of education depends on bold shifts from theory-heavy training to practice-rich, evidence-based learning. Our mission is to work with schools, universities, and teacher education programs to co-design and implement innovative pedagogies that prepare both educators and learners for real-world challenges. Whether through capacity-building workshops, curriculum design, or collaborative research, NGI helps institutions move from vision to practice. We invite education leaders, policymakers, and teacher educators to partner with us in shaping classrooms where both teachers and students learn by doing — building not only knowledge, but the confidence, skills, and mindsets needed for a rapidly changing world.

Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2021). Building a common core for learning to teach and connecting professional learning to practice. American Educator, 45(2), 10–14.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415.

Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2018). Redefining teacher: Re-imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching, 24(2), 178–192.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E., Duncan, R. G., & Chinn, C. A. (2021). Scaffolding and achievement in problem-based and project-based learning. Educational Psychologist, 56(4), 263–284.

IATED. (2022). Proceedings of the International Academy of Technology, Education and Development Conferences. Valencia: IATED Academy.

Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). Pearson Education.

Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving Schools, 19(3), 267–277.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Culturally sustaining pedagogy in practice. Harvard Educational Review, 91(1), 5–25.

McDonald, M., Kazemi, E., & Kavanagh, S. S. (2013). Core practices and pedagogies of teacher education: A call for a common language and collective activity. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(5), 378–386.

MDPI. (2023). Education Sciences – Special Issues on Innovation in Teacher Education. Basel: MDPI.

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., & Kinzer, C. K. (2015). Foundations of game-based learning. Educational Psychologist, 50(4), 258–283.

Subhash, S., & Cudney, E. A. (2018). Gamified learning in higher education: A systematic review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 192–206.

Zeichner, K. (2012). The turn once again toward practice-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(5), 376–382.

A beacon of excellence in the L&OD consultancy landscape. We bridge the gap between organizational objectives and outcomes through research-based interventions and “Data-Wisdom.”